The 2018 US Frontiers of Engineering Symposium, organized by the National Academy of Engineering and held at the MIT Lincoln Laboratory, brought together 111 early career engineers for an intensive 2-1/2 day symposium to discuss cutting-edge developments in four areas: Quantum Computers, the Role of Engineering in the Face of Conflict and Disaster, Resilient and Reliable Infrastructure, and Theranostics.

Below are a few sentences from the much longer talk I gave to the engineers there, which is titled “Engineering for the People: Putting Peace, Social Justice, and Environmental Protection at the Heart of Engineering”. The basic questions I posed to the attendees at the Symposium were: Why are we engineers? For whose benefit do we work? What is the full measure of our moral and social responsibility?

I don’t have to go back home to Mumbai, India to find technological inequality and its interplay with poverty, environmental injustice, and marginalization. I simply have to walk the streets of Phoenix, where many still have inadequate access to energy services in the desert summer; or San Francisco, where the tech-fueled gentrification and rising poverty has shocked even the UN’s poverty expert Philip Alston, who’s seen poverty all over the world; or Detroit, whose planning and cars helped create not only an American middle class but also urban sprawl and inertia for mitigating climate change; or Hale County in the Black Belt of Alabama, where even today, vast swaths of homes aren’t even built to code.

So, the legacy of engineering and science is not only replete with awe-inspiring achievements like refrigeration, computing, lasers, and getting to the moon, but is also full of mountaintop removal and poisoned waters, racism, and the continued development of the capacity to destroy life and the Earth. While these are certainly issues of social policy, they are also issues of science, engineering, and technology policy—they are issues of what we consider important to invest technically. I’ll go further and say that they are also issues with how we as engineers justify to ourselves the work we do. It is about our stake in the world we build.

It is easy for an engineer or company to say that what they are “just doing their job” when they are challenged about what they do…like building surveillance technologies or prisons or weapons or ways to drill for oil in the Arctic. But by saying it is “just a job,” engineers and companies shift the moral burden for bringing politically-charged objects into the world from themselves—those who actually do the designing and building—to those who order and pay for those things, like politicians. But people, politicians, and governments can talk all they want about doing something; they do not have the skills to actually do it. We do. And because engineering holds that power, engineering has the obligation to systematically do good.

This is the exact power what Google employees recently exerted, when they challenged management about Google’s involvement in providing AI expertise to a military pilot program called Project Maven, or Algorithmic Warfare Cross-Functional Team. Project Maven aims to “speed up analysis of drone footage by automatically classifying images of objects and people,” using computer vision. But several employees strongly protested to doing this work, and then wrote an internal petition to Google CEO Sundar Pichai, which started off with

We believe that Google should not be in the business of war. Therefore we ask that Project Maven be cancelled, and that Google draft, publicize and enforce a clear policy stating that neither Google nor its contractors will ever build warfare technology.

On 1 June, 2018, a New York Times headline read, “Google Will Not Renew Pentagon Contract That Upset Employees.” The power that engineering holds in society obligates it to systematically do good. And engineers are powerful.

But what is good? It’s subjective and normative, and questions of dual-use are real; building destructive capacity to one is strengthening national security to another…We need more spaces to have open and vigorous debates about what engineering is for.

[W]e live in a world with a lot of inequality and injustice, and unconsciously or otherwise, it’s a world that engineers have helped build. But it’s entirely reasonable to imagine engineering done to directly reduce inequality, injustice, suffering, and violence. This is the opposite of the kind of engineering where the benefits of our work trickles down to those who need it most, including non-humans. So, how do engineers push science, technology, and social policy to change how we do engineering to make more peaceful and just futures possible?

Engineers in the past have struggled with these very issues, and MIT engineers and scientists have been particularly influential. On the fourth of March, 1969, in the height of the anti-Vietnam War fervent, faculty and students at MIT shut down the entire Institute for a day to have a teach-in that featured panels on DoD- and ONR-sponsored research being done, including right here at Lincoln Laboratory. But this shutdown wasn’t only about research; it was about a battle over the values of our technological society [referencing Matthew Wisnioski’s wonderful book, Engineers for Change]. As part of this Science for the People movement, the MIT Fluid Mechanics Laboratory—which at the time included three full professors, three assistant professors, a support staff, and approximately 20 graduate students—this lab underwent a transformation. It changed the entire focus from fluids research for military purposes to four other fields: air pollution, water pollution, biomedicine, and desalination. There are many more examples like this.

[And there are wonderful examples of how engineering and science work is being done today to explicitly promote the values of peace, social justice, and environmental protection, from AAAS’s On-Call Scientists, to the work of SkyTruth, The Equitable Internet Initiative, and the US’s first peace engineering program at Drexel University.]

Maybe what I am saying challenges fundamental values and principles that guide science and technology investment in the US and the history of engineering professionalization. But the world we live in has in no small part been created by engineers, and engineers will continue to dictate the design and development of technologies that shape human relationship to the Earth and its people. So to infuse the engineer with ideals of justice, with practical tools to understand the impact of their work on people and the Earth, and with the ability to work intimately with those who have different kinds of knowledge, is to change the world. And I’d love to work with anyone on this project. So I leave you with questions I think all engineers should think about: Why are we engineers? For whose benefit do we work? What is the full measure of our moral and social responsibility?

(You can find a longer, but still edited, version of the talk at the National Academy of Engineering website, here.)

These final questions are those that drive the work we do in re-Engineered. They are questions that all engineers ought to reflect on, to make clear the assumptions they may be making in the work they are doing. I will continue to write about these questions in the posts ahead.

~Darshan

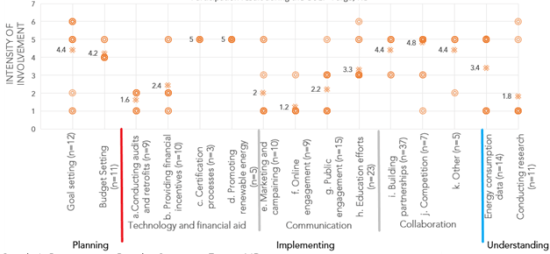

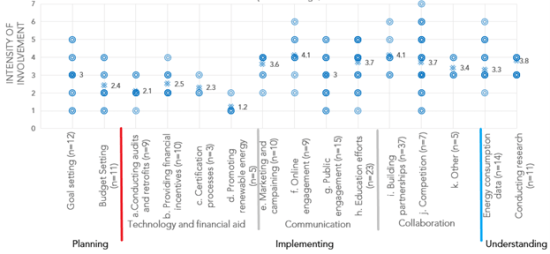

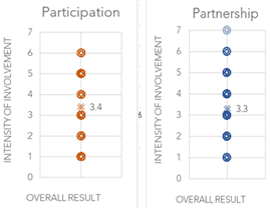

Figure 4: An example of the final scores of one community

Figure 4: An example of the final scores of one community